Note

Go to the end to download the full example code or to run this example in your browser via Binder.

Use rolling-ball algorithm for estimating background intensity#

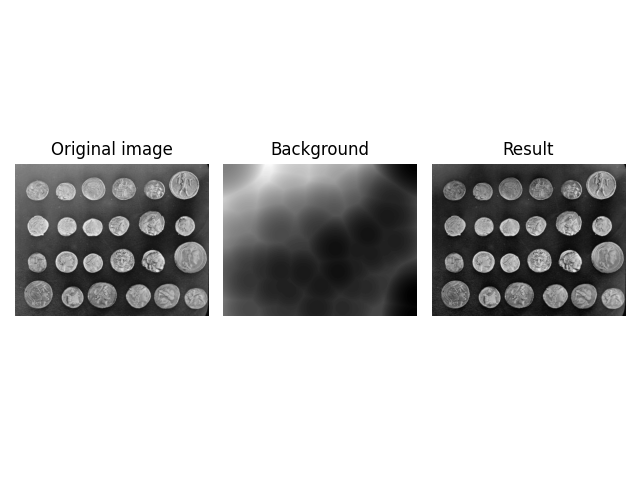

The rolling-ball algorithm estimates the background intensity of a grayscale image. It comes in useful, for instance, in case of uneven exposure, when subtracting the background is desirable. It is frequently used in biomedical image processing and was first proposed by Stanley R. Sternberg in 1983 [1].

The algorithm works as a filter: Think of the image as a surface that has unit-sized blocks stacked on top of each other in place of each pixel. The number of blocks, and hence surface height, is determined by the intensity of the pixel. To get the intensity of the background at a desired (pixel) position, we imagine submerging a ball under the surface at the desired position. Once it is completely covered by the blocks, the apex of the ball determines the intensity of the background at that position. We can then ‘roll’ this ball around below the surface to get the background values for the entire image. The larger the ball, the smoother the background.

scikit-image implements a generalized version of this rolling-ball algorithm, allowing you to work with n-dimensional images and to use not only balls, but other kernels as well. This way, you may directly filter RGB images or image stacks along any (or all) spatial dimensions.

Classic rolling ball#

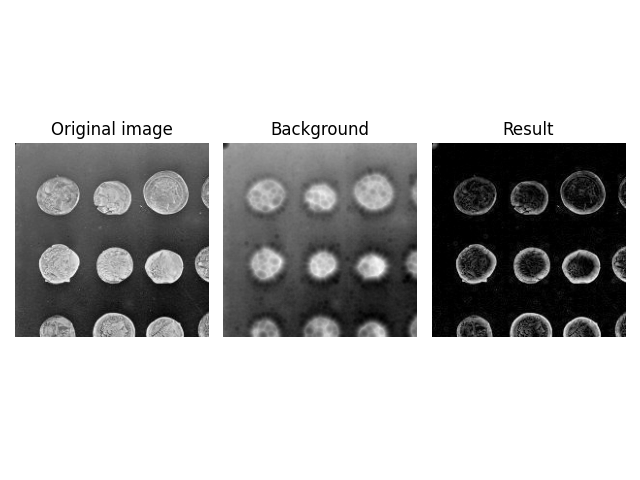

In scikit-image, the implementation assumes that your image background has low intensity (dark), whereas the features have high intensity (bright). If this is not your case, you first have to invert the image—we give an example of that further on.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pywt

import skimage as ski

def plot_result(image, background):

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=3)

ax[0].imshow(image, cmap='gray')

ax[0].set_title('Original image')

ax[0].axis('off')

ax[1].imshow(background, cmap='gray')

ax[1].set_title('Background')

ax[1].axis('off')

ax[2].imshow(image - background, cmap='gray')

ax[2].set_title('Result')

ax[2].axis('off')

fig.tight_layout()

image = ski.data.coins()

background = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(image)

plot_result(image, background)

plt.show()

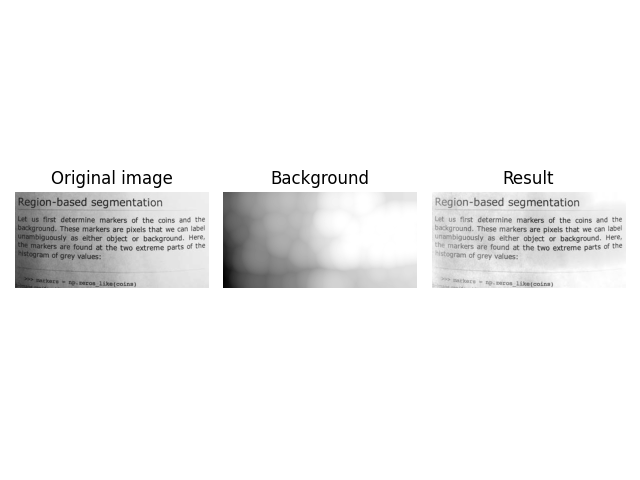

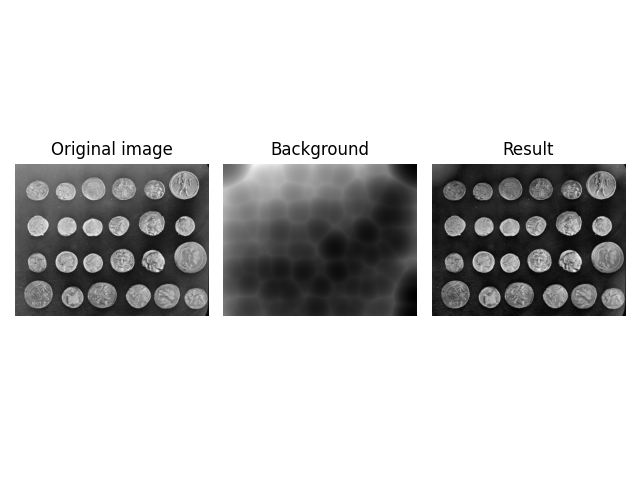

Bright background#

If you have dark features on a bright background, you need to invert the image before passing it to the rolling-ball filter, and then invert the result. This can be accomplished as follows:

image = ski.data.page()

image_inverted = ski.util.invert(image)

background_inverted = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(image_inverted, radius=45)

filtered_image_inverted = image_inverted - background_inverted

filtered_image = ski.util.invert(filtered_image_inverted)

background = ski.util.invert(background_inverted)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=3)

ax[0].imshow(image, cmap='gray')

ax[0].set_title('Original image')

ax[0].axis('off')

ax[1].imshow(background, cmap='gray')

ax[1].set_title('Background')

ax[1].axis('off')

ax[2].imshow(filtered_image, cmap='gray')

ax[2].set_title('Result')

ax[2].axis('off')

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

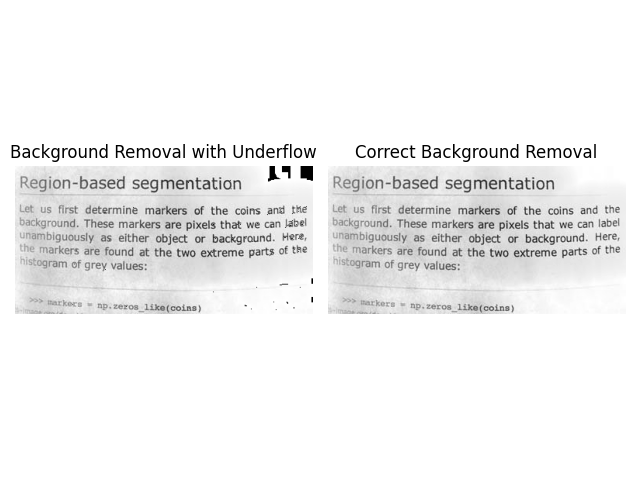

Be careful not to fall victim to an integer underflow when subtracting a bright background. For example, this code looks correct, but may suffer from an underflow leading to unwanted artifacts. You can see this in the top right corner of the visualization.

image = ski.data.page()

image_inverted = ski.util.invert(image)

background_inverted = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(image_inverted, radius=45)

background = ski.util.invert(background_inverted)

underflow_image = image - background # integer underflow occurs here

# correct subtraction

correct_image = ski.util.invert(image_inverted - background_inverted)

fig, ax = plt.subplots(ncols=2)

ax[0].imshow(underflow_image, cmap='gray')

ax[0].set_title('Background Removal with Underflow')

ax[0].axis('off')

ax[1].imshow(correct_image, cmap='gray')

ax[1].set_title('Correct Background Removal')

ax[1].axis('off')

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

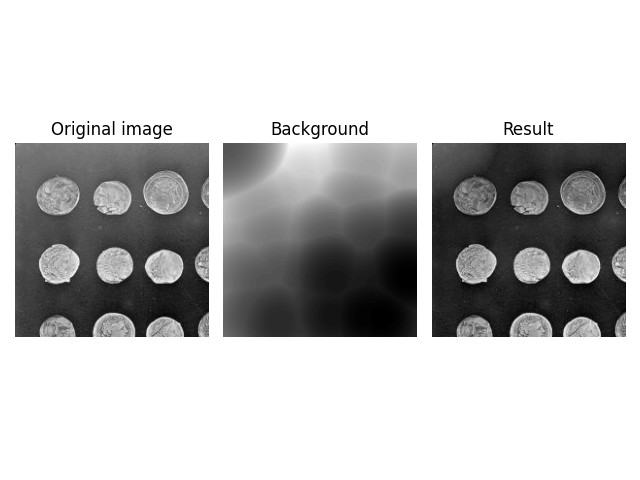

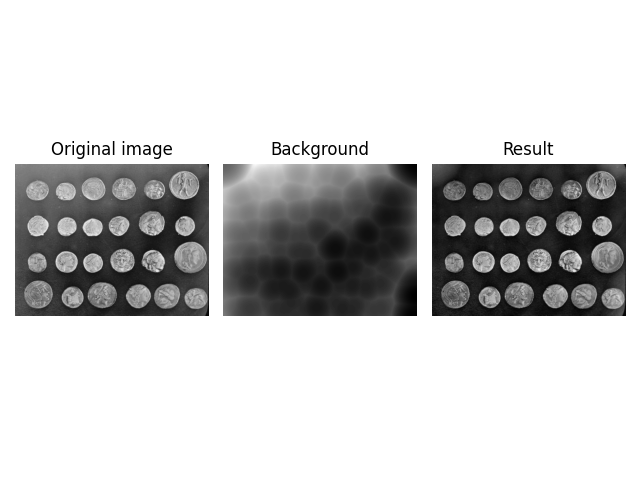

Image Datatypes#

rolling_ball can handle datatypes other than np.uint8. You can

pass them into the function in the same way.

image = ski.data.coins()[:200, :200].astype(np.uint16)

background = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(image, radius=70.5)

plot_result(image, background)

plt.show()

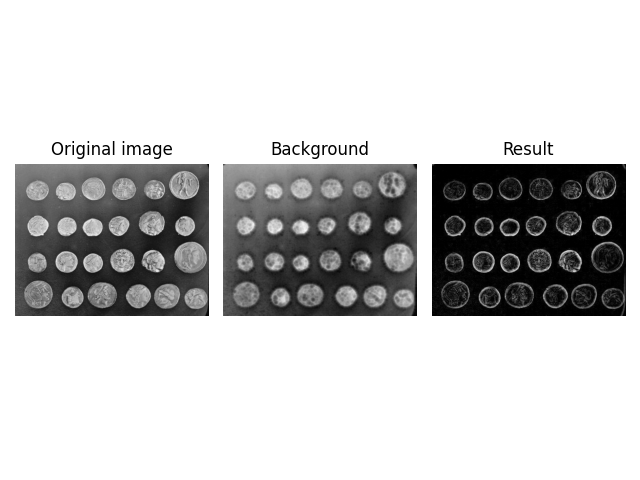

However, you need to be careful if you use floating point images

that have been normalized to [0, 1]. In this case the ball will

be much larger than the image intensity, which can lead to

unexpected results.

image = ski.util.img_as_float(ski.data.coins()[:200, :200])

background = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(image, radius=70.5)

plot_result(image, background)

plt.show()

Because radius=70.5 is much larger than the maximum intensity of

the image, the effective kernel size is reduced significantly, i.e.,

only a small cap (approximately radius=10) of the ball is rolled

around in the image. You can find a reproduction of this strange

effect in the Advanced Shapes section below.

To get the expected result, you need to reduce the intensity of the

kernel. This is done by specifying the kernel manually using the

kernel argument.

Note: The radius is equal to the length of a semi-axis of an ellipsis, which is half a full axis. Hence, the kernel shape is multiplied by two.

normalized_radius = 70.5 / 255

image = ski.util.img_as_float(ski.data.coins())

kernel = ski.restoration.ellipsoid_kernel((70.5 * 2, 70.5 * 2), normalized_radius * 2)

background = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(image, kernel=kernel)

plot_result(image, background)

plt.show()

Advanced Shapes#

By default, skimage.restoration.rolling_ball() uses a ball-shaped

kernel (surprise).

Sometimes, though, this can be too limiting—as in the example above,

because the intensity dimension has a different scale compared to

the spatial dimensions, or because the image dimensions may have

different meanings (e.g., one could be a stack counter in an image stack).

To account for this, skimage.restoration.rolling_ball() has a kernel

argument which allows you to specify the kernel to be used. A kernel must

have the same dimensionality as the image (i.e., the same number of

dimensions/axes).

To help with its creation, two kernel implementations are provided:

skimage.restoration.ball_kernel() specifies a ball-shaped kernel and

is used as the default kernel; skimage.restoration.ellipsoid_kernel()

specifies an ellipsoid-shaped kernel.

image = ski.data.coins()

kernel = ski.restoration.ellipsoid_kernel((70.5 * 2, 70.5 * 2), 70.5 * 2)

background = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(image, kernel=kernel)

plot_result(image, background)

plt.show()

You can also use skimage.restoration.ellipsoid_kernel() to recreate

the previous, unexpected result and see that the effective (spatial) filter

size was reduced.

image = ski.data.coins()

kernel = ski.restoration.ellipsoid_kernel((10 * 2, 10 * 2), 255 * 2)

background = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(image, kernel=kernel)

plot_result(image, background)

plt.show()

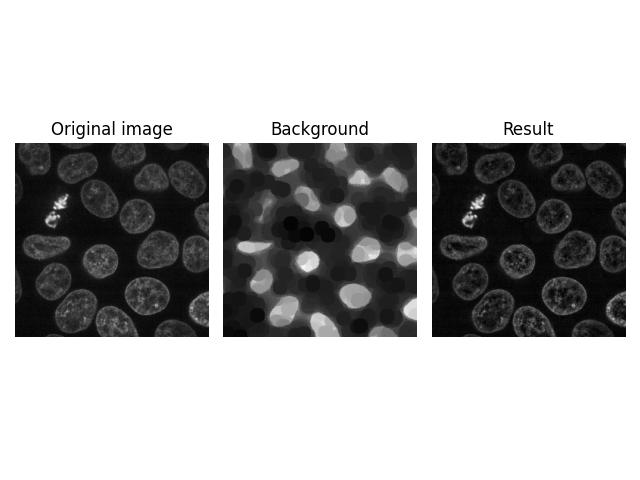

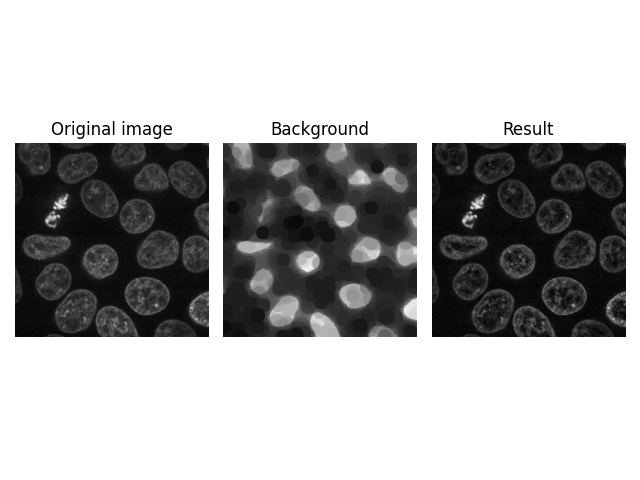

Higher Dimensions#

Another interesting feature of skimage.restoration.rolling_ball() is

that you can directly apply it to higher-dimensional images, e.g., a Z-stack

of images obtained in confocal microscopy. The number of kernel dimensions

must match that of image dimensions; in this case, the kernel is thus

3-dimensional.

image = ski.data.cells3d()[:, 1, ...]

kernel = ski.restoration.ellipsoid_kernel((1, 21, 21), 0.1)

background = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(image, kernel=kernel)

plot_result(image[30, ...], background[30, ...])

plt.show()

The above filter is actually applied to each image in the stack individually, since the kernel has size 1 along the Z axis.

To filter along all 3 dimensions at the same time, you must use sizes greater than 1 along all 3 dimensions.

Change the first line in the above code block.#kernel = ski.restoration.ellipsoid_kernel((5, 21, 21), 0.1)

Another possibility is to filter individual pixels only along the planar (Z) axis.

This change here will show a lot more clearly in the result.#kernel = ski.restoration.ellipsoid_kernel((100, 1, 1), 0.1)

1D Signal Filtering#

As another example of the n-dimensional feature of

rolling_ball, we show an implementation for 1D data. Here,

we are interested in removing the background signal of an ECG waveform

to detect prominent peaks (higher values than the local baseline).

Smoother peaks can be removed with smaller values of the radius.

x = pywt.data.ecg()

background = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(x, radius=80)

background2 = ski.restoration.rolling_ball(x, radius=10)

plt.figure()

plt.plot(x, label='original')

plt.plot(x - background, label='radius=80')

plt.plot(x - background2, label='radius=10')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Total running time of the script: (0 minutes 16.506 seconds)