Images are numpy arrays#

Images are represented in scikit-image using standard numpy arrays. This allows maximum inter-operability with other libraries in the scientific Python ecosystem, such as matplotlib and scipy.

Let’s see how to build a grayscale image as a 2D array:

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

random_image = np.random.random([500, 500])

plt.imshow(random_image, cmap='gray')

plt.colorbar();

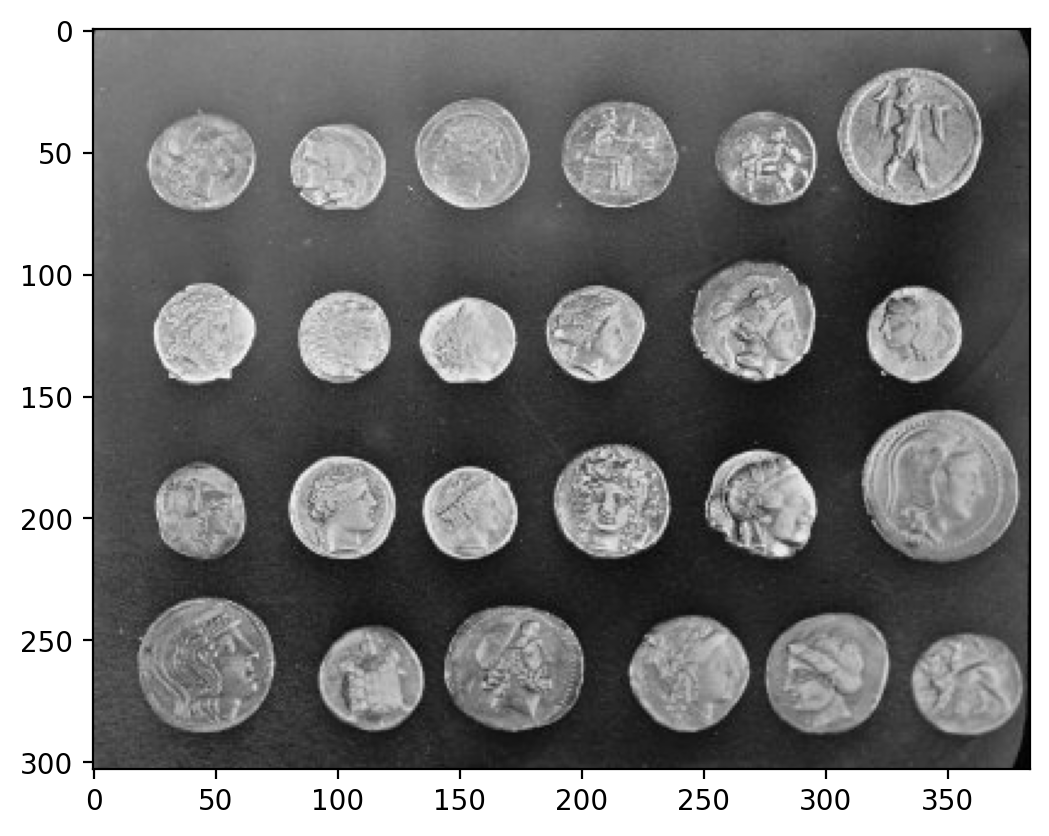

The same holds for “real-world” images:

from skimage import data

coins = data.coins()

print('Type:', type(coins))

print('dtype:', coins.dtype)

print('shape:', coins.shape)

plt.imshow(coins, cmap='gray');

A color image is a 3D array, where the last dimension has size 3 and represents the red, green, and blue channels:

cat = data.chelsea()

print("Shape:", cat.shape)

print("Values min/max:", cat.min(), cat.max())

plt.imshow(cat);

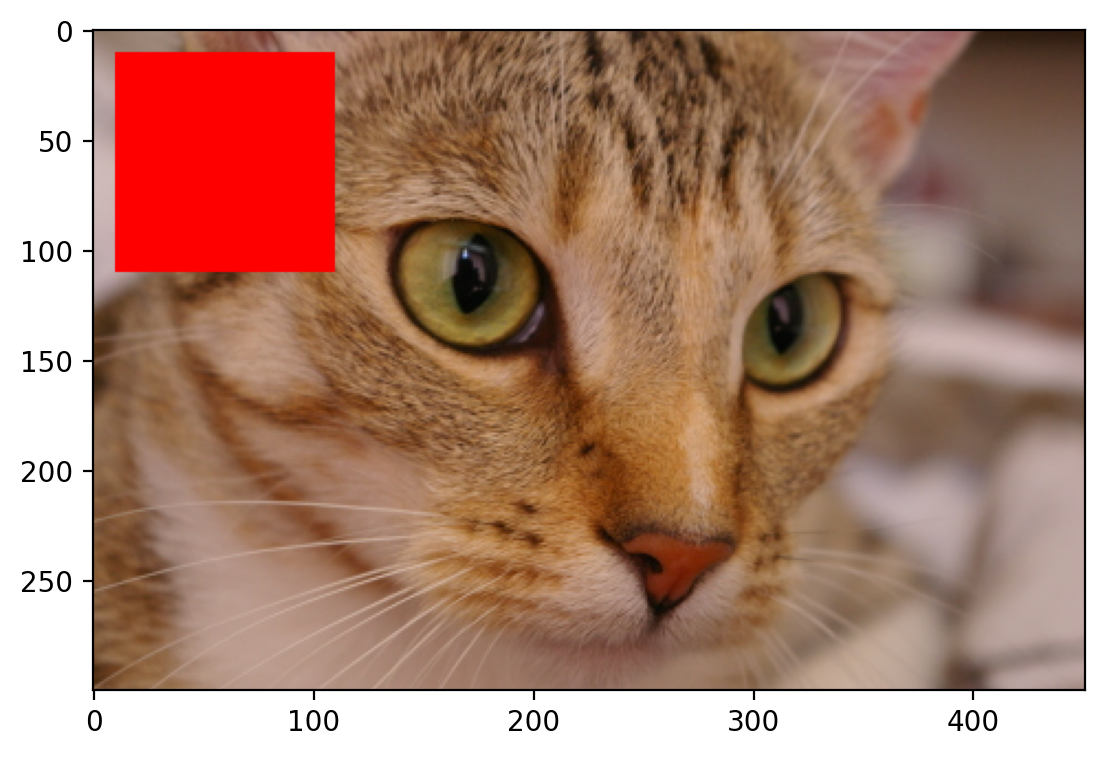

These are just NumPy arrays. E.g., we can make a red square by using standard array slicing and manipulation:

Images can also include transparent regions by adding a 4th dimension, called an alpha layer.

Other shapes, and their meanings#

Image type |

Coordinates |

|---|---|

2D grayscale |

(row, column) |

2D multichannel |

(row, column, channel) |

3D grayscale (or volumetric) |

(plane, row, column) |

3D multichannel |

(plane, row, column, channel) |

Displaying images using matplotlib#

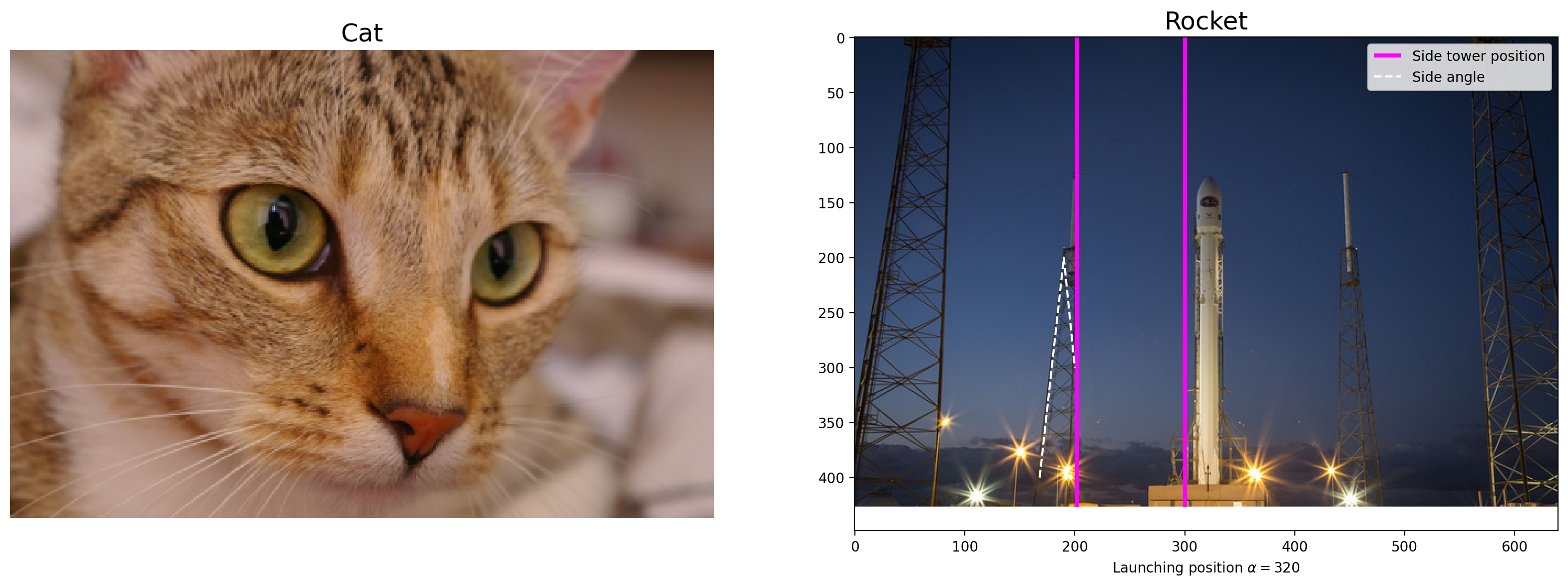

from skimage import data

img0 = data.chelsea()

img1 = data.rocket()

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

f, (ax0, ax1) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(20, 10))

ax0.imshow(img0)

ax0.set_title('Cat', fontsize=18)

ax0.axis('off')

ax1.imshow(img1)

ax1.set_title('Rocket', fontsize=18)

ax1.set_xlabel(r'Launching position $\alpha=320$')

ax1.vlines([202, 300], 0, img1.shape[0], colors='magenta', linewidth=3, label='Side tower position')

ax1.plot([168, 190, 200], [400, 200, 300], color='white', linestyle='--', label='Side angle')

ax1.legend();

For more on plotting, see the Matplotlib documentation and pyplot API.

Data types and image values#

In literature, one finds different conventions for representing image values:

0 - 255 where 0 is black, 255 is white

0 - 1 where 0 is black, 1 is white

scikit-image supports both conventions–the choice is determined by the

data-type of the array.

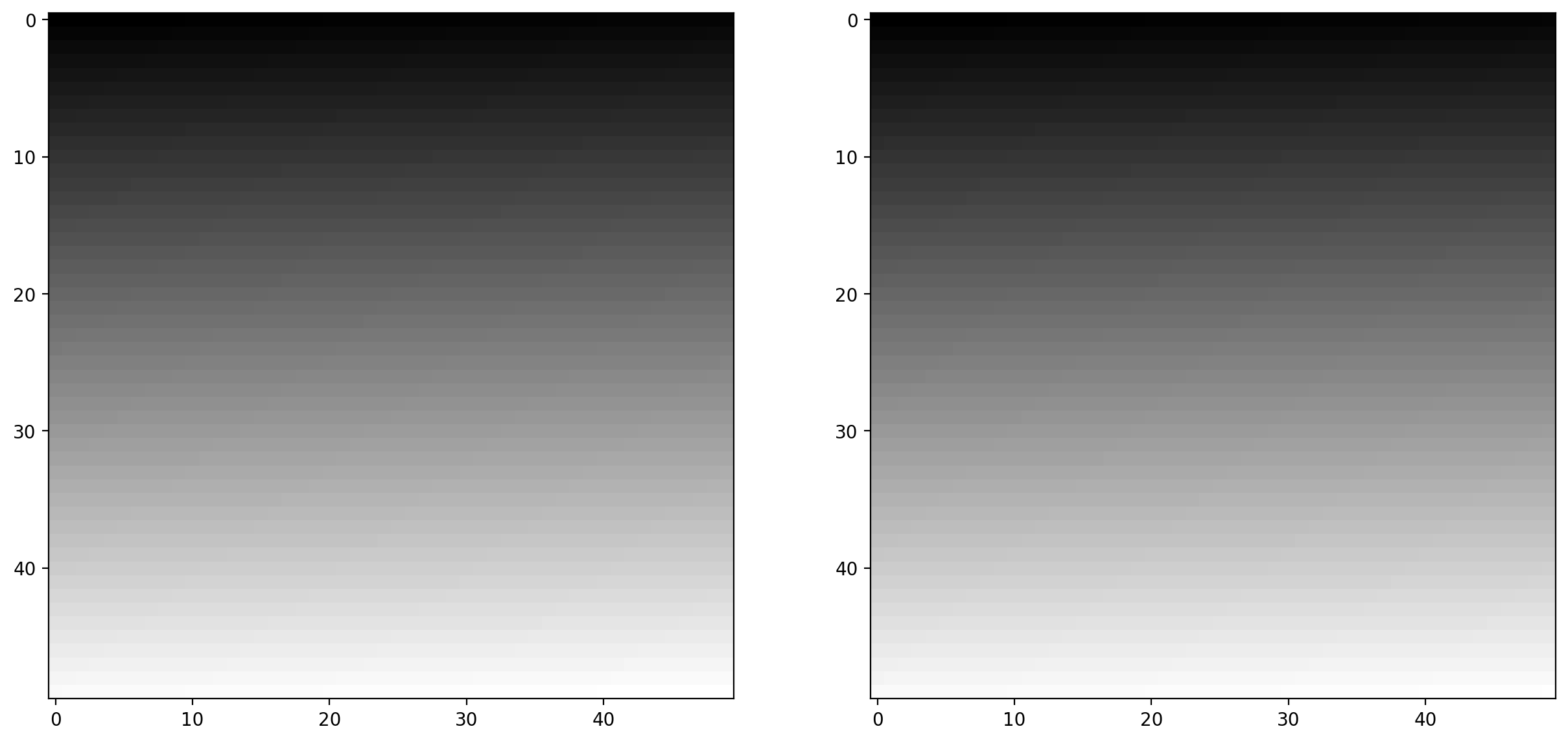

E.g., here, I generate two valid images:

linear0 = np.linspace(0, 1, 2500).reshape((50, 50))

linear1 = np.linspace(0, 255, 2500).reshape((50, 50)).astype(np.uint8)

print("Linear0:", linear0.dtype, linear0.min(), linear0.max())

print("Linear1:", linear1.dtype, linear1.min(), linear1.max())

fig, (ax0, ax1) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(15, 15))

ax0.imshow(linear0, cmap='gray')

ax1.imshow(linear1, cmap='gray');

The library is designed in such a way that any data-type is allowed as input, as long as the range is correct (0-1 for floating point images, 0-255 for unsigned bytes, 0-65535 for unsigned 16-bit integers).

You can convert images between different representations by using img_as_float, img_as_ubyte, etc.:

from skimage import img_as_float, img_as_ubyte

image = data.chelsea()

image_ubyte = img_as_ubyte(image)

image_float = img_as_float(image)

print("type, min, max:", image_ubyte.dtype, image_ubyte.min(), image_ubyte.max())

print("type, min, max:", image_float.dtype, image_float.min(), image_float.max())

print()

print("231/255 =", 231/255.)

type, min, max: uint8 0 231

type, min, max: float64 0.0 0.9058823529411765

231/255 = 0.9058823529411765

Your code would then typically look like this:

def my_function(any_image):

float_image = img_as_float(any_image)

# Proceed, knowing image is in [0, 1]

We recommend using the floating point representation, given that

scikit-image mostly uses that format internally.

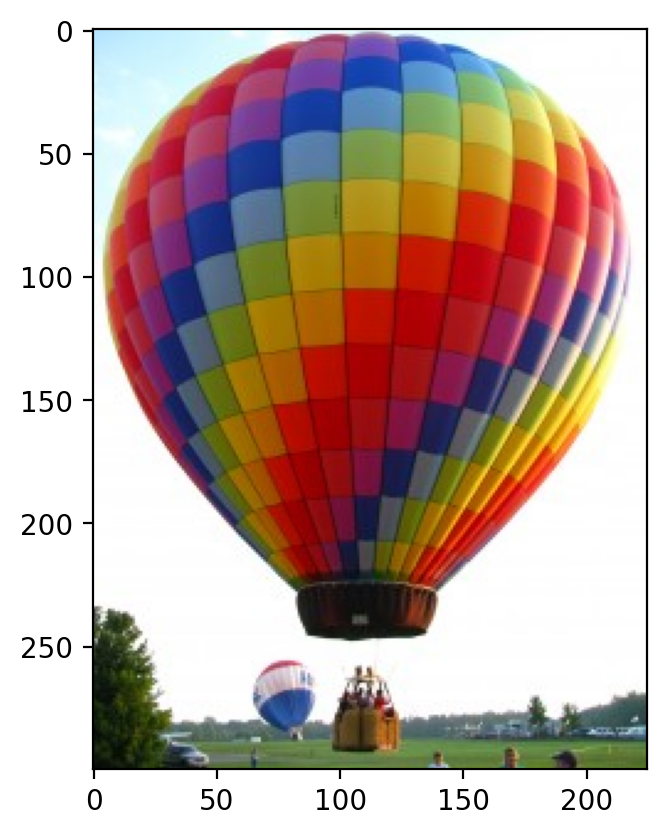

Image I/O#

Mostly, we won’t be using input images from the scikit-image example data sets. Those images are typically stored in JPEG or PNG format. Since scikit-image operates on NumPy arrays, any image reader library that provides arrays will do. Options include imageio, matplotlib, pillow, etc.

scikit-image conveniently wraps many of these in the io submodule, and will use whichever of the libraries mentioned above are installed:

from skimage import io

image = io.imread('../images/balloon.jpg')

print(type(image))

print(image.dtype)

print(image.shape)

print(image.min(), image.max())

plt.imshow(image);

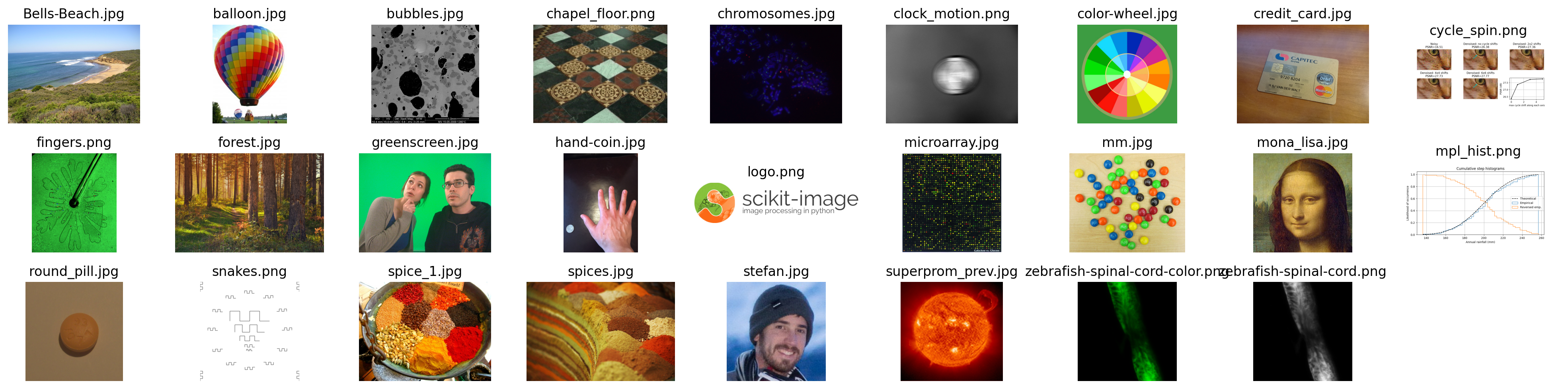

We also have the ability to load multiple images, or multi-layer TIFF images:

ic = io.ImageCollection('../images/*.png:../images/*.jpg')

print('Type:', type(ic))

ic.files

Type: <class 'skimage.io.collection.ImageCollection'>

['../images/Bells-Beach.jpg',

'../images/balloon.jpg',

'../images/bubbles.jpg',

'../images/chapel_floor.png',

'../images/chromosomes.jpg',

'../images/clock_motion.png',

'../images/color-wheel.jpg',

'../images/credit_card.jpg',

'../images/cycle_spin.png',

'../images/fingers.png',

'../images/forest.jpg',

'../images/greenscreen.jpg',

'../images/hand-coin.jpg',

'../images/logo.png',

'../images/microarray.jpg',

'../images/mm.jpg',

'../images/mona_lisa.jpg',

'../images/mpl_hist.png',

'../images/round_pill.jpg',

'../images/snakes.png',

'../images/spice_1.jpg',

'../images/spices.jpg',

'../images/stefan.jpg',

'../images/superprom_prev.jpg',

'../images/zebrafish-spinal-cord-color.png',

'../images/zebrafish-spinal-cord.png']

import os

f, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=3, ncols=len(ic) // 3 + 1, figsize=(20, 5))

# subplots returns the figure and an array of axes

# we use `axes.ravel()` to turn these into a list

axes = axes.ravel()

for ax in axes:

ax.axis('off')

for i, image in enumerate(ic):

axes[i].imshow(image, cmap='gray')

axes[i].set_title(os.path.basename(ic.files[i]))

plt.tight_layout()

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

/Volumes/zorg/mb312/.virtualenvs/skimage-tutorials/lib/python3.12/site-packages/skimage/io/collection.py:316: FutureWarning: The plugin infrastructure in `skimage.io` is deprecated since version 0.25 and will be removed in 0.27 (or later). To avoid this warning, please do not pass additional keyword arguments for plugins (`**plugin_args`). Instead, use `imageio` or other I/O packages directly. See also `skimage.io.imread`.

self.data[idx] = self.load_func(fname, **kwargs)

Aside: enumerate#

enumerate gives us each element in a container, along with its position.

animals = ['cat', 'dog', 'leopard']

for i, animal in enumerate(animals):

print('The animal in position {} is {}'.format(i, animal))

The animal in position 0 is cat

The animal in position 1 is dog

The animal in position 2 is leopard

Exercise: draw the letter H#

Define a function that takes as input an RGB image and a pair of coordinates (row, column), and returns a copy with a green letter H overlaid at those coordinates. The coordinates point to the top-left corner of the H.

The arms and strut of the H should have a width of 3 pixels, and the H itself should have a height of 24 pixels and width of 20 pixels.

Start with the following template:

def draw_H(image, coords, color=(0, 255, 0)):

out = image.copy()

...

return out

Test your function like so:

cat = data.chelsea()

cat_H = draw_H(cat, (50, -50))

plt.imshow(cat_H);

Exercise: visualizing RGB channels#

Display the different color channels of the image along (each as a gray-scale image). Start with the following template:

# --- read in the image ---

image = plt.imread('../images/Bells-Beach.jpg')

# --- assign each color channel to a different variable ---

r = ... # FIXME: grab channel from image...

g = ... # FIXME

b = ... # FIXME

# --- display the image and r, g, b channels ---

f, axes = plt.subplots(1, 4, figsize=(16, 5))

for ax in axes:

ax.axis('off')

(ax_r, ax_g, ax_b, ax_color) = axes

ax_r.imshow(r, cmap='gray')

ax_r.set_title('red channel')

ax_g.imshow(g, cmap='gray')

ax_g.set_title('green channel')

ax_b.imshow(b, cmap='gray')

ax_b.set_title('blue channel')

# --- Here, we stack the R, G, and B layers again

# to form a color image ---

ax_color.imshow(np.stack([r, g, b], axis=2))

ax_color.set_title('all channels');

Now, take a look at the following R, G, and B channels. How would their combination look? (Write some code to confirm your intuition.)

from skimage import draw

red = np.zeros((300, 300))

green = np.zeros((300, 300))

blue = np.zeros((300, 300))

r, c = draw.disk(center=(100, 100), radius=100)

red[r, c] = 1

r, c = draw.disk(center=(100, 200), radius=100)

green[r, c] = 1

r, c = draw.disk(center=(200, 150), radius=100)

blue[r, c] = 1

f, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3)

for (ax, channel) in zip(axes, [red, green, blue]):

ax.imshow(channel, cmap='gray')

ax.axis('off')

Exercise: Convert to grayscale (“black and white”)#

The relative luminance of an image is the intensity of light coming from each point. Different colors contribute differently to the luminance: it’s very hard to have a bright, pure blue, for example. So, starting from an RGB image, the luminance is given by:

Use Python 3.5’s matrix multiplication, @, to convert an RGB image to a grayscale luminance image according to the formula above.

Compare your results to that obtained with skimage.color.rgb2gray.

Change the coefficients to 1/3 (i.e., take the mean of the red, green, and blue channels, to see how that approach compares with rgb2gray).

from skimage import color, img_as_float

image = img_as_float(io.imread('../images/balloon.jpg'))

gray = color.rgb2gray(image)

my_gray = ... # FIXME

# --- display the results ---

f, (ax0, ax1) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(10, 6))

ax0.imshow(gray, cmap='gray')

ax0.set_title('skimage.color.rgb2gray')

ax1.imshow(my_gray, cmap='gray')

ax1.set_title('my rgb2gray')